INDIGENOUS STEWARDSHIP & CONSERVATION IN A CHANGING WORLD

By Nicole Heller, AMLT Research Associate

Nicole Heller is the Director of Conservation Science at Peninsula Open Space Trust. She received her PhD in Biological Sciences from Stanford University. She has worked on biodiversity protection in California ecosystems for nearly 2 decades, and has published widely on topics ranging from climate change adaptation to ant behavior.

When I first learned the science of conservation biology as a student in the early 1990s, the emphasis was on getting people out of the equation. “Ideal nature,” the thing to be restored, did not include human beings. Conservation work was about protecting the land, removing all human impacts, and then leaving nature alone to return itself to its historic composition.

Leaving nature alone to heal itself, however, has not proved viable. Persistent stresses of the modern globalized landscape, including exotic invasive species that tend to dominate systems, the loss of top predators, and now climate change, have made it hard for species to survive in their historic locales. Now more than ever conservationists find themselves needing to intervene in ecosystems in order to sustain native plants and animals.

As I have written about elsewhere, this may seem like a crisis and a paradox: “natural” is both an absence of human influence, and simultaneously that which can only be maintained through human influence (see Heller and Hobbs 2014). But it ceases to be a paradox when we realize that this biodiversity that we seek to protect is itself the product of human interaction.

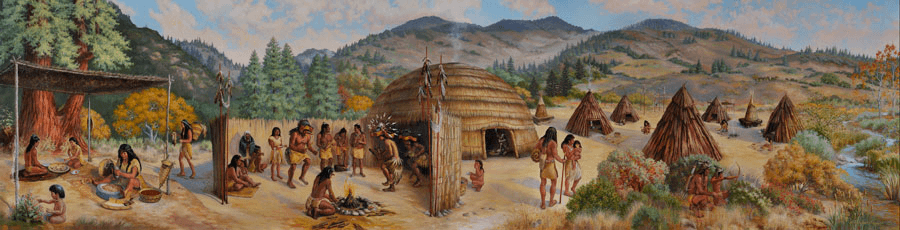

The work of Kat Anderson, and other ethnoecologists and anthropologists working around the world, is changing the way we understand biodiversity protection. Indigenous people have been intimately involved in shaping ecosystems. Through burning, pruning, tilling and seeding, they fostered the species they cared about and controlled the species that were not useful or would dominate if not tended. This Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) provides a different way to think about people in nature. Within this way of thinking, California Indians were a keystone species within California ecosystems and the disruption of these people and their relationships with other creatures has been part of what has driven biodiversity decline. Restoring people’s ability to play this role in ecological systems may be key to maintaining biodiversity in the modern landscape.

Today’s landscape is different than the historic landscape. The climate is changing rapidly because of greenhouse gas emissions. The density of people is hundreds to thousands of time greater than it was 500 years ago in California. Methods of stewardship have to look different, but they can be built on the types of relationships between humans and other creatures that were practiced by California Indians.

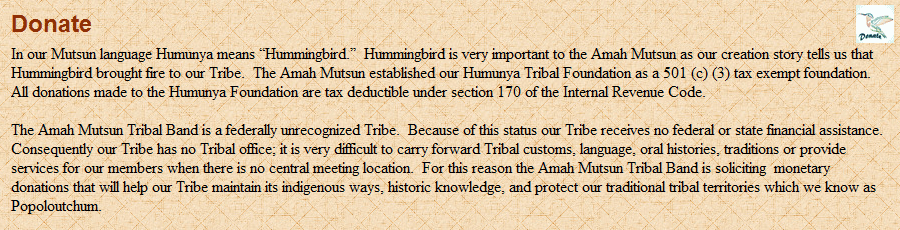

The practices the Amah Mutsun Land Trust is sharing provide a model of how to relate to the land adaptively, gently, and with humility. They provide a model that will be useful to foster native biodiversity with an open mind and open heart through the rapid change of the 21st century. TEK provides a model for developing a practice that can bring more people into conservation work and help to bridge the divide between nature and human (or, also, culture) that drives many of our environmental and social challenges. I appreciate the opportunity to work with the AMLT to re-learn these relationships, adapt them to the modern landscape, and integrate them into conventional conservation practice.

Reference

HELLER, N. E. and HOBBS, R. J. (2014), Development of a Natural Practice to Adapt Conservation Goals to Global Change. Conservation Biology, 28: 696–704. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12269