YERBA SANTA, A MEDICINAL PLANT EXTRAORDINAIRE

By M. Kat Anderson, AMLT Technical advisor

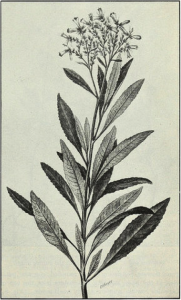

Yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum)

Photo courtesy Franco Folini, CC BY 2.0

M. Kat Anderson is a prominent ethnoecologist currently working with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. She has worked alongside California Indian people for over 25 years to document and support indigenous stewardship. Dr. Anderson is author of the book “Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources,” as well as many articles about California ethnobotany and traditional resource and environmental management.

One of the more common shrubs growing in California’s chaparral and woodlands, yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum) is also one of the state’s preeminent medicinal plants. In pre-mission California, there was hardly a tribe with yerba santa in its territory that did not use this plant for medicine. Its leaves were gathered up and down the state by diverse tribes in northwestern California, the Sierra Nevada foothills, southern California, and by the ancestors of the Amah Mutsun on the Central Coast. Today, the Amah Mutsun continue to gather and prepare yerba santa in part through the activities of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust.

Traditional Uses

People knew yerba santa by its varnished leathery leaves with serrated edges and its coiled inflorescences of showy tubular whitish to pale-blue flowers. They gathered its leaves and used them to treat a surprisingly broad range of ailments: colds, throat and bronchial affections, grippe, asthma and other respiratory ailments, catarrh, stomach aches, vomiting, diarrhea, aching or sore spots, wounds, abrasions, and the pain and swelling associated with fractured bones.

The Amah Mutsun applied warmed yerba santa leaves to the forehead to treat headaches, chewed or smoked the leaves to relieve asthma and coughs, made a decoction for rheumatism and tuberculosis and purification of the blood, and made a tea to wash the eyes and treat eye ailments. They combined yerba santa with other herbs to heal infected sores.

Today the Amah Mutsun and other tribes are teaching the virtues of this plant to the younger generations, continuing ancient healing traditions. In summer 2015, the Amah Mutsun Land Trust Native Stewardship Corps gathered yerba santa on the flanks of Mt. Humunhum, the location of the Mutsun creation story. In fall 2015, Native Stewards again gathered and tended yerba santa, and relearned its use in a traditional remedy.

“Holy Herb”: Yerba santa and European settlers

The plant’s Spanish name (yerba means “herb” and santa means “sacred”) dates to the time of the Spanish missions, when this “holy herb” was an important part of the padres’ herbal medicine repertoire. It held an esteemed place alongside herbs brought from Europe, Asia, and Mexico, such as rosemary, horehound, foxglove, Castillan rose, saffron, cilantro, and castor oil. Yerba santa proved efficacious in the missions for treatment of headaches and many kinds of lung problems.

It was the Indians, of course, who taught the missionaries this plant’s medicinal virtues. Dr. Cephas L. Bard (1894) an early western physician, said of the California missionaries: “they admitted in the treatment of diseases the superiority of the virtues of the domestic remedies in the hands of the natives, by not only applying to them, but by entrusting them, at times with the care of those in the infirmaries.”

Early non-Indian settlers were also taught the plant’s healing powers; they valued it for its expectorant properties, employed it for throat and bronchial ailments, and also used it as a bitter tonic. Because its odor was aromatic and its taste balsamic and sweetish, it was used to mask the repugnant taste of other medicines.

By the late 1800s, yerba santa was widely accepted by American physicians as a leading agent for all respiratory conditions, for treating kidney conditions and rheumatic pain, and for healing hemorrhoids when other sources failed. On this basis, the United States medical establishment adopted it as an official medicine in the United States Pharmacopoeia. In an 1894 speech before the Southern California Medical Society, Dr. Cephas L. Bard, the society’s outgoing president, called yerba santa one of the three “most valuable vegetable additions which have been made to the Pharmacopoeia during the last twenty years.”

Yerba santa displaying insect damage and sooty fungus.

Photo courtesy Bri Weldon, CC BY 2.0

Yerba Santa and Fire: Rejuvenating potential

Indian and non-Indian herbalists have strict requirements for the use of yerba santa in their medicines: they want relatively young, shiny leaves free of any disease because these contain more of the plant’s active principles. Today, mature yerba santa plants are often spindly, with leaves only at the tips of the branches and bare limbs below, and the leaves frequently have a high percent of damage from a pathogen called sooty fungus. We know that in past times, California tribes regularly burned plant communities supporting plants valued for food, basket making, and medicine, and often used fire on specific patches of valued plants.

The fire had the effect of rejuvenating the plants. It ensured good production of the most useful plant parts, and eliminated diseases. It is therefore likely that in the past, yerba santa benefitted—at least indirectly—from Indian burning. Yerba santa seeds remain viable in the soil for decades, and they germinate readily during the first spring after a fire. Further, older plants can regenerate from rhizomes following the burning of their above-ground parts.

Participants in the 2015 Native Stewardship Corps confirmed the problem of overgrown yerba santa during the course of stewardship and gathering activities. They found that untended plants in mature patches were virtually unusable, having sooty fungus and significant insect damage. Recently mowed patches, however, yielded the fresh new growth and healthy leaves the Stewards required for collection.

Given its fire-adapted nature and the value assigned to it as a medicine, it is likely that many Native Californians even targeted yerba santa for burning, and did so specifically to keep the plants healthy and maximize their production of leaves that could be harvested for medicine. Although we do not have a lot of direct evidence of burning yerba santa for medicine, we do know that the Pomo periodically burned yerba santa patches to kill pathogens and add nutrients to the soil. Perhaps such use of fire is the secret to restoring the health of yerba santa today on traditional lands where it grows.

Indian burning represents an often under-appreciated aspect of the use of native plants for medicinal purposes. It was an indigenous management strategy that guaranteed the existence of an adequate supply of plant material with the proper characteristics. It thus went hand-in-hand with knowledge of a plant’s medicinal properties. Today we would do well to appreciate the importance of both of these aspects of native plant use and to recognize that knowledge of both plants’ medicinal properties and their care in their natural habitats originated with Native Californians.

To learn more about how Native Americans enriched the practice of American medicine in the United States and gave us conservation, harvest, and management strategies, see the April 2016 issue of the Journal of Medicinal Plant Conservation.

References

Bard, C.L. 1894. A contribution to the history of medicine in southern California. Annual Address of the Retiring President of the Southern California Medical Society, Delivered at San Diego, August 8, 1894. Digitized by Google.

Barrett, S.A. and E.W. Gifford. 1933. Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee. 2(4):117-376.

Bocek, B.R. 1984. Ethnobotany of Costanoan Indians, California, based on collections by John P. Harrington. Economic Botany 38(2):240-255.

Crellin, J.K. and J. Philpott. 1990. A Reference Guide to Medicinal Plants: Herbal Medicine Past and Present. Duke University Press, Durham.

Engelhardt, Fr. Z. 1929. San Antonio de Padua: The Mission in the Sierras. Mission Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, California.

Grieve, M. 1931. A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-Lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs & Trees with All their Modern Scientific Uses. Volume 2. Hartcourt, Brace & Co.. Republished in 1971 by Dover Publications, Inc., New York.

Harrington, J.P. 1942. Cultural Element Distributions: XIX, Central California Coast. Anthropological Records 7:1-46.

Harrington Notes, Reel 61, Frame 184, Pages 1-2.

Henkel, A. 1911. American medicinal leaves and herbs. U.S. Department of Agriculture Bureau of Plant Industry Bulletin No. 219. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Howard, J.L. 1992. Eriodictyon californicum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2013, March 26].

Hutchens, A.R. 1973. Indian Herbalogy of North America. Merco, Ontario, Canada.

Moermann, D.E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Peri, D.W., S.M. Patterson, and J.L. Goodrich. 1982. Ethnobotanical Mitigation Warm Springs Dam—Lake Sonoma California. Ed. E. Hill and R.N. erner. Unpublished report of Elgar Hill, Environmental Analysis and Planning, Penngrove, CA.