History

Introduction

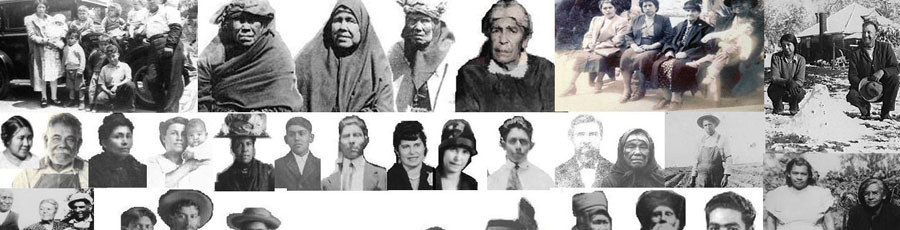

The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band currently has an enrolled membership of nearly 600 BIA documented Indians. These are the Previously Recognized Tribal group listed by the Indian Service Bureau (now known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs) as the “San Juan Band.” All lineages comprising the “Amah Mutsun Tribal Band” are the direct descendents of the aboriginal Tribal groups whose villages and territories fell under the sphere of influence of Missions San Juan Bautista (Mutsun) and Santa Cruz (Awaswas) during the late 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.

As a result of the Congressional Appropriation Acts of 1906 and 1908 our Tribe came under the legal jurisdiction of the Indian Service Bureau (BIA), and the Reno and Sacramento Indian Agencies until 1927. Our Tribe was never terminated by any Act or intent of the Congress, however, we remained a landless Tribe since our Federally Acknowledged status began in 1906. As a result of the Congressional California Indian Jurisdictional Act of 1928, both living members and direct ancestors enrolled with the BIA between 1930 and 1932. Our members also enrolled between 1948 to 1955 and during the third enrollment period between 1968 to 1970.

Our Tribe is currently listed with the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs as Petitioner #120 as we are seeking status clarification to have our Recognized status restored by the Secretary of the Interior.

Pre-Contact / Pre-Mission

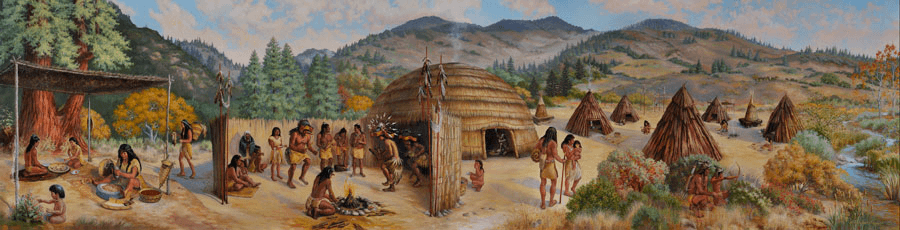

The Amah Mutsun Tribe had an extensive history of communal activity, shared cultural understanding and collective rituals and beliefs. The Amah Mutsun occupied the San Juan Valley for thousands of years before the Spanish arrived in the late 1700’s.

The Amah Mutsun community was originally made up of approximately 20 to 30 contiguous villages stretched across the Pajaro River Basin and surrounding region. Members of these different villages were united by shared cultural practices and tribal traditions. Their mutual religious practices, method of fishing and hunting, ceremonial dress, craftsmanship, and shelter set them apart from other tribes of California.

The Amah Mutsun community was originally made up of approximately 20 to 30 contiguous villages stretched across the Pajaro River Basin and surrounding region. Members of these different villages were united by shared cultural practices and tribal traditions. Their mutual religious practices, method of fishing and hunting, ceremonial dress, craftsmanship, and shelter set them apart from other tribes of California.

Most significantly, Amah villages were distinct from tribes outside their valley because of their unique language; no other Indian tribe spoke Mutsun. While the Costanoan/Ohlone language family was made up of eight separate languages, including Mutsun, each language was “as different from one another as Spanish is from French” in the Romance language group. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the Mutsun language had been spoken in the San Juan Valley for thousands of years, indeed it was one of the first American Indian languages extensively studied in North America.

The Amah Mutsun Tribe had been drawn to the triangle of land formed by the Monterey Bay and the Pajaro and San Benito rivers due to the abundance of water and fish. The Tribe was geographically isolated from its neighbors due to the physiography of the San Juan Valley (Tratrah). However, these abundant lands later attracted other settlers who would drastically change the lives of the Amah Mutsun.

Some Tribal ways of life for the Mutsun were that Chiefs were responsible for feeding visitors; providing for the impoverished; directing ceremonial activities, and directing hunting, fishing, gathering and warfare expeditions. Warfare was not uncommon for the Mutsun. Infringement of territorial rights was the most frequent cause of war. Because the territory of the Mutsun was so valuable in terms of food supply, many other tribes coveted it. The Mutsun insured a sustained yield of plant and animal foods by careful management of the lands. Controlled burning of extensive areas of land was carried out each fall to promote the growth of seed bearing annuals. The Mutsun diet consisted of acorns, hazelnuts, blackberries, elderberries, strawberries, gooseberries, madrone berries, wild grapes, wild onions, cattail roots chuchupate (herb), wild carrots, deer, elk, antelope, bear, rabbit, raccoon, squirrel, rat, mouse, sea lion, whale, duck, geese and a variety of birds. Also eaten were salmon, steelhead, sardine, shark, swordfish, trout, lampreys, mussels, abalone, octopus, grasshoppers, caterpillars and most varieties of reptiles. The Mutsun never ate eagles, owls, raven, buzzards, frogs or toads.

Family dwellings were domed structure thatched with tule, grass, ferns, etc. A small sweathouse was constructed by digging a pit in the bank of a stream and building the remainder of the structure against the bank. Dance enclosures were constructed in the middle of the village and were circular or oval in shape and consisted of a woven fence of brush or laurel branches about four and one-half feet high. There was a single doorway and a small opening opposite it. Tule boats (balsas) were used by the Mutsun for transportation, fishing and hunting. Bow and arrows, spears, nets and basket traps were used for hunting and fishing. Fish poisoning and fishhooks were also used. Tools were made of bone, wood, rocks and minerals. Baskets were used in the collection, preparation, and storage of food.

Missions Santa Cruz: 1791–1834 and San Juan Bautista: 1797–1834

The Spanish started their colonization of Central California in 1770 founding Mission San Carlos Borremeo del Rio Marmelo (Carmel) by Fr. Junipero Serra, second of the 21 missions. The Mission system was conceived such that no mission would be more than a day’s ride from another. Mission Santa Cruz was founded in 1797. Construction of Mission San Juan Bautista began in 1797. The Mission was located in this part of the valley in order to be near indigenous Indian villages, which became the source of labor and converts for the Mission priests.

The Spanish started their colonization of Central California in 1770 founding Mission San Carlos Borremeo del Rio Marmelo (Carmel) by Fr. Junipero Serra, second of the 21 missions. The Mission system was conceived such that no mission would be more than a day’s ride from another. Mission Santa Cruz was founded in 1797. Construction of Mission San Juan Bautista began in 1797. The Mission was located in this part of the valley in order to be near indigenous Indian villages, which became the source of labor and converts for the Mission priests.

The Amah Mutsun people were aware of the actions of the Spanish, many village and religious sites were abandoned and spies were sent to the Missions at Monterey and Santa Cruz. They witnessed the destruction of the sacred tree near Monterey and the subjugation of the Rumsen (Carmel), Awaswas (Santa Cruz), and neighboring villages. When the Spanish came to Tratrah they conducted a campaign to subjugate the Amah Mutsun. First they invaded the religious shrines of the Amah replacing them with Christian icons. When this was not totally successful the Spanish soldiers forcibly removed the Indians from their villages and brought them to the Mission compound, separating children from parents. The Amah were considered Mission property upon baptism, and were not permitted to return to their Tribal Lands.

Many of the Christianized Indians, who were called “neophytes,” attempted to flee the harsh conditions and slavery of the Mission. As a result, Spanish military expeditions were routinely dispatched to look for runaways and bring them back to the Mission.

Some of the Amah took up weapons against the Spanish. First were the Ausaima; in 1802 after a series of battles the Ausaima were defeated. Some records indicate that they may have moved to the central valley near the Merced River. The Orestac also battled the Spanish, but with little success. Arrows, stones and tomahawks are of little consequence when facing guns, swords and mounted cavalrymen fitted with lances. Under these oppressive conditions, the Amah were forced to conduct their tribal activities and speak their language in secret. This practice became a part of the discrimination and persecution of the Amah Mutsun. At the same time, while life at the Mission was repressive, the plight they experienced broke down any barriers that may have existed between the inhabitants of the different Amah Mutsun villages. This facilitated the public re-emergence of the Tribe in the 20th century.

Although the stated goal of the Missions was to return land to the Indians, no land was ever provided. During the Mission period over 19,421 Indians died at Mission San Juan Bautista and approximately 150,000 Indians died in California. According to anthropologist estimates the California Indian population was reduced from 350,000 to 200,000 during this time.

Mission Records

The San Juan Bautista Mission priests were excellent record-keepers, and they maintained meticulous documentation of many Amah Mutsun activities. In 1841, Father Felipe de la Cuesta, a priest of Mission San Juan Bautista, published the Mutsun language in Europe, which was followed by a much later release in America. Father Felipe de la Cuesta translated prayers, songs, doctrines, confessions, and all primary vocabulary.

The Mission library contained records about the local Amah, including records of births, baptisms, marriages and funerals, as well as punishment and imprisonments. From these records, journals and other documents, it is apparent that the priests attempted to inculcate the Amah Mutsun with a new value system, so as to “civilize” them. Necessarily, Tribal activity was forbidden. Neophytes were not allowed to speak the Mutsun language, conduct Tribal ceremonies, or use their own Indian names. They were punished if these rules were broken. In addition to battling assaults on their culture, the Indians were also afflicted with foreign diseases brought by the Spanish, including smallpox, measles and venereal diseases. As a result, by 1833 there had been a total of 3,396 baptisms, 858 marriages and 19,421 deaths at Mission San Juan Bautista.

The Mexican Period: 1834–1848

Life for the Amah Mutsun changed when, in early 1820’s, Mexico won independence from Spain and more Mexicans began to arrive in the San Juan Valley. The Mexicans consolidated control of outlying lands, and by 1833, they forced the Mexican Government to turn over and secularize the Mission. Shortly thereafter, the remaining Amah Mutsun were finally allowed to leave the Mission compound. However, their problems continued with the Mexican authorities. Although the Mexicans promised a return of ancestral land, the officials reneged under pressure from Mexican and Spanish citizens who wanted land. Forced to scavenge for land and work, the Amah Mutsun settled for a time in the town of San Juan Bautista. It is much more complicated than this as the Indians had already begun working on the Rancheros

During the Mexican period Indians were forced to work under a peonage-system. They worked in slave or near slave-like conditions performing work such as shearing sheep, herding cattle, cutting lumber, harvesting crops, pounding grain into flour, building houses, tanning hides, cleaning houses, serving meals, and making tile and adobe bricks.

During the Mexican period shipping traffic increased. Ships from the eastern coast would bring manufactured goods such as fish hooks, cotton cloth, blankets, shoes, exotic spices, etc. to the California Coast. These items were traded for the skins of wolverines, fisher martens, mink, beaver otters and whale oil. The trapping/hunting of these species greatly reduced the populations of these animals.

During this period of time Native plants such as oak trees, were logged for fuel, carts and other purposes. Native plants were eaten by cattle and sheep before they could seed and the population of these plants were drastically reduced.

Throughout the Mexican period measles, pneumonia, diptheria, and venereal and other diseases spread throughout the Native population. During the Mexican period it is estimated that the population of California Indians was reduced by 100,000; their population went from 200,000 to 100,000 in this short period of time.

The Arrival of the Americans: 1848

In 1848, the Amah Mutsun were disturbed again when Anglo settlers came to the region. A story within the Amah Mutsun Tribe is that when the Indians heard that the Americans were coming to California they gathered together in the corner of a room and cried because they were certain the Americans would kill them all. It wasn’t long before the rush for gold forcibly displaced the Tribe’s member’s from their new homes. They were rounded up like cattle and forced to work, and their children were kidnapped and enslaved. Many were simply killed.

The Anglos had no respect for the culture and traditional ways of the aboriginal people, nor for their rights to occupancy of the land. Anglos, furthermore, were afraid of the California Indians from the outset. Due to the Anglos’ experiences with the Plains Indians, the California Indians were treated with brutality.

In early 1850’s, both the Federal and the State governments concluded there was an “Indian problem.” To deal with this “problem” both governments developed their own solution. The federal government became alarmed by reports of violence against the aboriginal populations, and in 1852 it established special military reservations to remove some of the Indians from the general population. At these military compounds, the federal government conducted treaty negotiations with local Indians. Some of the San Juan Indians participated in the negotiations serving as interpreters between the Americans and Tribal Chiefs and were signatories to the treaties signed near Pleasanton. Immediately after the treaties were completed, a powerful California business and political lobby quashed all hopes of getting the treaties ratified in the Senate (see 1851-52; California’s response to Federal Treaties Negotiated with the Indians, page 23) The U.S. Senate placed the treaties in confidential files and ordered that they be sealed for 50 years. In 1905 the Senate voted to remove the injunction of secrecy but the proposed reservation land was now spoken for by the Anglo settlers. Because the treaties were never signed all California Indians not living on reservations, such as the Mutsun, became landless Indians.

The California solution to the Indian problem was that the Governor of California, Peter H. Burnett, signed an Executive Order to Exterminate all Indians (see Early California Laws and Policies Related to California Indians, Kimberly Johnson-Dodds, California State Library, California Research Bureau):

That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races, until the Indian race becomes extinct, must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.

Governor Peter H. Burnett, January 7, 1851

As a result of this Executive Order, the state of California paid $.25–$5.00 bounty for every killed Indian and funded military expeditions for the purpose of exterminating Indians. During this campaign the State paid over $1,200,000.00. A report by the California State Library shows that over $259,000 were spent on efforts in Monterey County and Mariposa County. County lines were drawn differently during this time, but Monterey County incorporated the traditional tribal territory of the Amah Mutsun. These campaigns continued until 1859.

During the last half of the 19th century, state hostility toward Indians continued, manifesting itself in numerous legal restrictions that deprived Indians of civil rights, voting rights and basic judicial protections (see Early California Laws). Their subsistence was again threatened by the government, which considered ejecting all Indians from the state. Obviously, this environment was not conducive to Indian proclamations of sovereignty, demands for ancestral lands, or declarations or Tribal identity. This pervasive, statewide persecution sent an unambiguous message to the Amah Mutsun: hide or be eradicated/exterminated.

An act for the relief of the Mission Indians in the State of California: 1891

In 1891 the President of the United States signed an act for the relief of the Mission Indians in the State of California. (Robin, link to Mission Indian Act of 1891. word document ) This Act provided that “a just and satisfactory settlement of the Mission Indians residing in the State of California upon reservations which shall be secured to them as hereafter provided.” and ” That it shall be the duty of said commissioners to select a reservation for each band or village of the Mission Indians residing within said State, which reservation shall include, as far as practicable the lands and villages which have been in the actual occupation and possession of said Indians, and which shall be sufficient in extent to meet their just requirements, which selection shall be valid when approved by the President and Secretary of the Interior.”

It appears as if though the Act for the Relief of the Mission Indians of the State of California was relegated to those mission tribes of southern California who obtained land and have reservations. It also appears that the State of California opposed other Mission Tribes obtaining lands or a reservation.

The Amah Mutsun believe that this Act gives Federal Recognition Status to the Amah Mutsun Tribe and that our Tribe was illegally denied a reservation in both San Juan Bautista and Santa Cruz.

The Era of Ascencion

Through the 1900 Census and a separate census authorized by Congress in 1906 that targeted non-reservation California Indians, the federal government took a renewed and somewhat more positive interest in Indians.

The Tribe’s re-emergence during this period can be heavily attributed to Ascencion Solorsano de Cervantes, around whose home much Tribal activity was centered. Ascencion’s house became a place where members came on a daily basis to enlist Ascencion’s support and to share news with other members. Ascencion became a repository for Tribal history, learning stories from others and passing on traditions and Tribal lore to the next generation. She took on the responsibility for finding employment, food and medicine for members of the Tribe who needed her help. Her leadership in the first three decades of the 20th century was critical to the future of the Tribe, and coincided with this time when the Tribe’s members were finally able to practice their culture publicly.

Alfred Kroeber extended the first and second volumes of Father Felipe de la Cuesta’s work on the Mutsun language, and Tribal customs, in the early 1920’s. Subsequently, John Peabody Harrington continued his research by conducting follow-up interviews with Ascencion Solorsano and the San Juan community throughout the 1930’s. Mr. Harrington’s body of work provides one of the best linguistic and culturally rich set of records, covering a specific Tribe and their language.

Mr. J.P. Harrington and the Smithsonian Institute employed Ascension Solorsano’s granddaughter, Martha Herrera. They met when Mr. Harrington went to New Monterey to interview Ascension before her death. Martha was hired as his secretary and traveled with him to various California Missions transcribing notes from Spanish to English. He also requested other information ranging from plants and their medicinal uses to recipes. Mr. Harrington’s daughter donated letters written by Martha, her mother and other family members to the Santa Barbara Mission.

Mr. J.P. Harrington and the Smithsonian Institute employed Ascension Solorsano’s granddaughter, Martha Herrera. They met when Mr. Harrington went to New Monterey to interview Ascension before her death. Martha was hired as his secretary and traveled with him to various California Missions transcribing notes from Spanish to English. He also requested other information ranging from plants and their medicinal uses to recipes. Mr. Harrington’s daughter donated letters written by Martha, her mother and other family members to the Santa Barbara Mission.

By 1928, many Tribal members were not afraid to cooperate with federal authorities and were included in the 1928 Indian Enrollment Process. On their enrollment forms, members were accurately identified as “Mission Indian, San Juan Bautista” for the first time. At least 65 members of the Amah Mutsun were enrolled, including the ancestors of several prominent Mutsun families of today. By this time, the Amah Mutsun had resurfaced as a cohesive Tribal unit, allowing itself to be publicly visible to whites and Hispanics after so many years of suppression and compulsory sequestration.

Ascencion had succeeded in reinvigorating Amah Mutsun identity and raising non-Indian awareness of the Tribe. According to one historian, her reburial was “one of the largest funerals in the history of the County” that paid “honor not to one person only, but to the entire Tribe.” In 1995, Ascencion Solorsano was elected into the Gilroy, California Hall of Fame. In 2003, the first middle school built in 30 years in Gilroy was named Ascencion Solorsano Middle School. This state of the art school is a part of the Gilroy Unified School District.

The Dorrington Report

In 1915 Lafeyette A. Dorrington was assigned as a special agent with the Indian Services in California. Indian Services was later named the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the U.S. Department of the Interior. In 1923 Dorrington served as Superintendent in the newly created Sacramento office of the Indian Agency. As Superintendent, Dorrington was instructed to determine the land needs for California Tribes under his jurisdiction. On June 23, 1927 Dorrington submitted his final report which listed approximately 230 tribes; these tribes represented over 11,500 Indians. (See Dorrington Report.)

Each of these tribes met the federal definition of a tribe as they were originally a body of people bound together by blood ties who were socially, politically, and religiously organized, who lived together in a defined territory and who spoke a common language or dialect. Finally, the federal government maintained the responsibility for a trust relationship for all these Tribes. This meant the United States acknowledged it had a responsibility to protect the sovereignty of each tribal government, to manage the prosperity and resources of Indian tribes and to protect their religion and culture.

Of the 230 Tribe’s listed approximately 45 Tribes, about 3,000 Indians, were provided land. The tribes for which land was purchased are now federally recognized Tribes and have a special, legal relationship to the U.S. Government. These tribes are also recognized as having tribal sovereignty which provides for direct government-to-government relationships with the U.S. government and that no decisions by the federal government can be made about tribal land or tribal members without their consent. With few exceptions, the 8,500 Indians who did not receive land and their descendents remain landless through today. As a result of the Dorrington report the federal government illegally dropped its trust responsibility and federal recognition status of the approximate 185 tribes; including the federal recognition of the Amah Mutsun.

The fact that the Indian Service agency even accepted the Dorrington report as a final document is incredulous. This report had a life or death impact for many California tribes. For the most part Dorrington provided a one to two sentence report on each Tribe. For the Amah Mutsun, who were identified in the Dorrington report as the San Juan Baptista Band, Dorrington’s wrote: “In San Benito County, we find the San Juan Baptista Band, which reside in the vicinity of the Mission San Juan Baptista, which is located near the town of Hollister. These Indians have been well cared for by Catholic priests and no land is required.”

Based on Dorrington’s “final report,” which contained no evidence, supporting documentation or confirmation of any type for his fraudulent statements, the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band’s federal recognition status was illegally terminated

The Amah Mutsun were never notified by Dorrington that he was tasked with determining the land needs of California Tribes. Also, the Indian Field Services provided no notification to our Tribe that we were being dropped from federal recognition and no due process was followed. By law only an Act of Congress can terminate a federally recognized tribe. The Indian Field Services made the determination that there was no need to purchase land for the Amah Mutsun Tribe with no site visit or review, no documentation or evidence to support their decision was provided and no internal report or field study was developed. This egregious act has had a devastating impact on approximately seven generations of our Tribal members. Our language, songs, religion, oral histories, traditional beliefs, dances, medicines, foods, etc., were all negatively impacted by this fraudulent government report.

Finally, there is no record of Dorrington ever visiting the territories between San Francisco and San Luis Obispo. A review of the 18 boxes of archival records of L.A. Dorrington, held at the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration in San Bruno, California, clearly verifies this point. Dorrington did not provide land to any of the tribes along the central coast and as a result there are no Indian reservations or rancherias within this 230 mile central coast area.

The Modern Era

Since Ascencion’s death in 1930, the Tribe has become stronger, and a series of leaders have ushered in a new era of Tribal growth. Ascencion’s daughter, Maria Dionicia, followed later by Mutsun members Josefa Buelna, Tony Corona, Joseph Mondragon, Charlie Higuera and Valentin Lopez, have taken on Ascencion’s role as spiritual and figurative heads of the Tribe.

Starting in the latter part of the 1920’s and continuing up to the mid 1960’s many Tribal members worked on the ranches in and around the Hollister and Gilroy. In particular the George Schrepfer ranch located at the south end of Gilroy on the Monterey Highway, played an important role for many Mutsun lineages. Ranch owner, George Schrepfer, had a deep empathy and concern for the indigenous Indians of San Juan Bautista. As a result he employed many of the Mutsun members during various times of the year, particularly during the harvest time. They picked grapes, walnuts, tomatoes and prunes. During difficult periods of the year when members did not have money for rent they could always go to George Schrepfer’s ranch and put up a tent until better times arrived. It was not unusual to see up to a dozen tents there at one time. We have documented 11 Mutsun family groups who lived and worked on the Schrepfer Ranch from the late 1920’s to the mid 1960’s. George Schrepfer’s daughter, Barbara, signed a notarized affidavit, where she tells of her recollections during this period and identifies many of the Mutsuns who worked on this ranch.

The 1930s brought regular Tribal gatherings at marriages, funerals and baptisms, as it was required that all members assemble for the funeral of another. Many of these events were used to conduct informal Tribal business and exchange family and other Tribal information. The Tribe also remained in contact to communicate employment opportunities and inquire about one another’s health.

The 1940’s saw young Amah Mutsun’s leave for war, and those who remained worked to assist the war effort in our factories. In 1947, the Tribe participated in federal litigation to recover compensation from the government for promises it had made during the 1850 negotiations.

During the 1950s and 1960s, gatherings of the Amah Mutsun Tribe were held as part of the San Juan Bautista Powwow, an annual three-day celebration at which members would participate in activities to celebrate their Amah Mutsun heritage.

In 1991 the Amah Mutsun Tribe formed a government and passed a constitution. Irene Zwierlein was recognized as Chairwoman at this time. In 1992 the Amah Mutsun submitted documents requesting to have their federal recognition restored. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band is currently listed as number two on the “Ready for Active Consideration” which means the review of our petition should begin sometime within the next few years.

On March 18, 2000, a meeting was called to inquire about Chairwoman Zwierlein’s activities and leadership regarding the Tribe. This meeting was tape recorded. Rather than provide answers to Council Members questions she resign as Chairwoman. Council recommended that she submit her resignation in writing which she did prior to leaving the meeting. Immediately after resigning she regretted her decision and submitted over the course of the next few months four fraudulent documents to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). These documents claimed she was still Chairwoman of the Amah Mutsun and stated that some members of the Tribe formed a splinter group.

Upon her resignation Vice-Chair Charles Higuera assumed the Chairperson position per our Tribal Constitution. Upon learning of the fraudulent documents Tribal Council attempted to obtain copies of the documents and to bring this information to the BIA. In July 2003, Valentin Lopez was elected Chairman and continued the effort to obtained and present these documents to the BIA. When they were presented to the BIA they took no action. The Tribe attempted to get others governmental entities to take action and they did not. The Tribe then arranged to have the documents examined by a forensic document examiner who certified that the documents were indeed fraudulent. Once again we attempted to get a governmental entity to take action and were unsuccessful. Following this we decided to go to the press and the Gilroy Dispatch published an article on the findings and soon Former Congressman Richard Pombo ordered the Department of Interior, Office of Inspector General to conduct an investigation into the fraudulent documents. The findings of this federal investigation concluded that Ms. Zwierlein had submitted four fraudulent documents in an effort to give the appearance that she was still the legitimate Chairwoman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. Next we attempted to get the BIA to file charges against Irene Zwierlein but they took no action. To find out more on the fraudulent documents go to Forgery Claim Blurs Tribe’s Fate, Tribal Papers Forged, and Congressman Michael M. Honda’s letter demanding action.

Today the Amah Mutsun Tribe is an active community of nearly 600 members, each of whom can trace their individual descent directly to a Mission San Juan Bautista Indian and/or a Mission Santa Cruz Indian. Some within the Tribe can tie their descendency to other Missions as well. In addition to the annual gatherings discussed above, the Tribe also holds regular membership meetings of the Tribal Council. The Council is responsible for governing the day-to-day operations of the Tribe. The Tribal Council works closely with its elders, and within the traditional Tribal structure, to resolve member concerns and carry on the business of the Tribe.

The Amah Mutsun have developed special relationships with Pinnacles National Monument, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, California Department of Parks and Recreation, U.C. Santa Cruz, U.C. Berkeley, U.C. Davis and many county and city entities. Finally, we have developed relationships with conservation and land trust organization to help protect our traditional tribal territory and Tribal interests. For these we are very grateful.

Related Links

Native American Holocaust Exterminate Them! The California Story